INDUSTRY INSIGHTS

How Fast Can You Really Build a Data Center?

The Operational Framework Behind Extreme Compression

When you ask most data center contractors how long a project takes, the answer is predictable: two to three years. Katie Coulson, Executive Vice President and General Manager of Skanska Advanced Technology, operates differently. Her projects compress significantly faster without sacrificing safety or quality.

The philosophy separating her approach from standard practice: "If everything works, we're probably not trying hard enough." This isn't about working harder. It's about working differently. Speed becomes a diagnostic tool, revealing where processes are broken.

Understanding this framework matters enormously. The workflows enabling faster execution are fundamentally different from traditional construction sequences.

TL;DR: How to Actually Build a Data Center Fast

Speed in data center construction isn’t magic. It’s operational discipline. Katie Coulson (Skanska) shows that 2–3 year timelines collapse ONLY when you rebuild the entire workflow, not just push people harder.

Here’s the real playbook behind extreme compression:

Speed is a diagnostic tool - If nothing breaks, you’re not pushing hard enough.

Subs > spreadsheets - Using the same high-trust mechanical/electrical crews across states eliminates onboarding friction and drives consistent speed.

Procurement starts during design - Pre-qualify vendors early, standardize components, and compress buyout from 6–8 weeks to days.

Prefab runs on BIM - Offsite mechanical/electrical assemblies reduce on-site work, improve safety, and remove weeks from the schedule.

Labor arbitrage matters - Build skids in low-cost regions, ship to high-cost ones, and let local crews focus on final integration.

Owner-furnished equipment is the critical path - Weekly vendor reviews and proactive tracking prevent the schedule from collapsing.

Culture beats tools - No software fixes a slow organization. Speed emerges from teams who experiment, communicate aggressively, and adapt daily.

Bottom line: Contractors don’t lose to Skanska on tech. They lose on operational sequencing, vendor relationships, and culture. If you aren’t re-engineering these foundations, speed stays out of reach.

Why Speed Remains Rare in Construction

The data center boom creates urgency, yet most general contractors still operate on traditional timelines. This gap is structural.

Subcontractor Ecosystem

Speed requires crews who understand your culture and have executed similar work before. Trust matters more than cost when the schedule is compressed. Skanska works with the same specialized electrical and mechanical subs across multiple states precisely because these crews understand what the client requires. They reduce onboarding friction and enable rapid execution in unfamiliar markets. Without this relationship depth, moving fast becomes nearly impossible.

Supply Chain Brittleness

In high-tech construction, owners furnish 40 to 60 percent of equipment. When cleanroom subs, equipment vendors, and electrical suppliers operate on their own schedules, one bottleneck cascades across the entire timeline. Coordinating these dependencies requires constant communication and weekly reviews. Most general contractors lack the institutional bandwidth to manage this complexity. A single delayed shipment can consume weeks of schedule buffer.

Procurement Complexity

Procurement still lives in spreadsheets and email at most contractors. Buyout cycles stretch across weeks because vendors aren't pre-qualified and pricing frameworks don't exist in advance. By the time an RFQ goes out, weeks of design work have already consumed the schedule buffer. This sequential approach creates a bottleneck that forces everything downstream to wait.

These barriers explain why competitors cannot match Skanska's speed. They also create opportunity for those willing to solve them.

Move One: Parallel Procurement and Pre-Qualification

How It Works

Traditional construction follows a sequential pattern: design completes, specifications finalize, vendors bid, responses arrive weeks later, negotiations occur, orders placed, manufacturing begins. The cycle consumes six to eight weeks.

Fast-track construction inverts this. Procurement begins during design, not after it.

The mechanism:

During design, identify components that repeat across projects (electrical equipment, mechanical systems, cooling infrastructure)

Pre-qualify vendors and develop pricing frameworks based on preliminary specifications

Vendors provide budgetary quotes knowing final specs will closely match initial scope

When design completes, the bid phase compresses to days instead of weeks

Why Standardization Matters

Katie noted this approach works particularly well in standardized data center work: "There are a lot of owners who are not having so many different types of buildings or different types of things; they're really building similarly so that it's a lot easier to price." When projects follow similar patterns, pre-qualification becomes increasingly effective.

What This Means for Technology

Tools that succeed in this space don't replace RFQs; they enable pre-qualification workflows and maintain vendor relationships across multiple cycles. The companies winning in fast-track construction have built institutional vendor relationships. Technology should help them scale those relationships.

Move Two: Subcontractor Lock-In and Geographic Portability

Why Relationships Matter More Than Commodities

A subcontractor who has executed three data center projects with your company understands your safety expectations, quality standards, and timeline pressure. They know which details matter. They are an extension of your team.

Skanska pays a premium to work with the same specialized subs across multiple projects because the premium is less expensive than onboarding new crews and managing performance variance.

Katie stated directly:

"We definitely have some contractors that we work with consistently on these tech type projects, and they understand really that speed that it takes. And so especially if we're going into different markets we have some contractors that want to go with us to those different markets because they understand how the projects work, how to get the people there."

The Two-Tier Geographic Model

When expanding into new markets, Skanska brings core subcontractors (often at higher labor rates than local subs) and supplements them with local crews for routine work. The specialized work stays with proven teams. This creates strategic partners who travel and tactical resources that provide geographic coverage.

What This Means for Technology

Tools managing subcontractor workflows often assume commodity labor where workers are interchangeable. That assumption fails in fast-track construction. The constraint isn't finding workers; it's finding crews with the right experience and cultural fit. Technology that helps contractors maintain and scale relationships with proven subs solves a real problem.

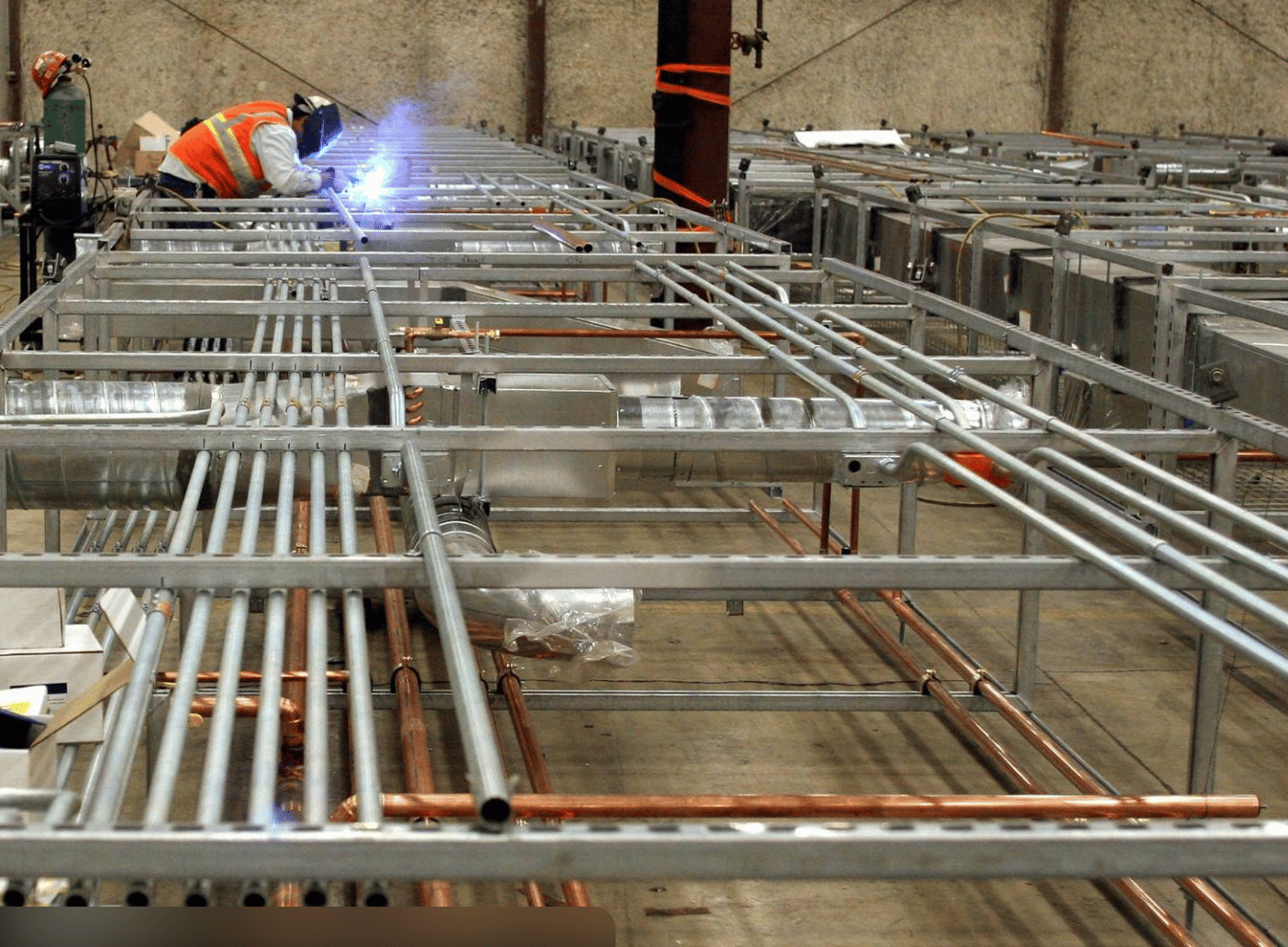

Move Three: Prefabrication Synchronized with BIM Data

The Assembly Approach

Katie described offsite mechanical assembly:

"We can have equipment that needs to be put on there. So maybe it's pumps and just really kind of like the mechanical systems that we're putting on there. And we're doing all of the piping, all the electrical, all the heat trace, right. And then being able to have that. And then you really have the connection, then ready to then be able to ship down."

This approach compresses on-site assembly work dramatically. The factory manufactures precise skids to BIM-derived specifications. The site crew focuses on final connections and integration.

The Safety Multiplier

Work occurring at height on-site happens on the ground in controlled environments

Fewer workers at elevation reduces accident risk

Quality improves when done in factory conditions

Assemblies can be tested before shipping to site

Katie mentioned prefabricated ductwork "so large you could drive a semi through it." This isn't standard HVAC assembly; it's engineered components built to exact specifications. The ductwork ships to the site ready for installation, eliminating weeks of fabrication.

The Critical Enabler: BIM Data

Prefabrication requires detail. The factory cannot build to ambiguity. BIM models provide the precision needed to manufacture offsite components that will fit and function on-site. Coordination matters enormously. Prefab schedules must align with site construction sequences. The prefab shop cannot build three months ahead of when components are installed.

What This Means for Technology

Schedule tools that treat prefabrication as an afterthought miss the central coordination challenge. Winning technology integrates prefab manufacturing timelines with site construction sequences in real time. It shows when materials arrive, where they stage, and how they integrate with other trades.

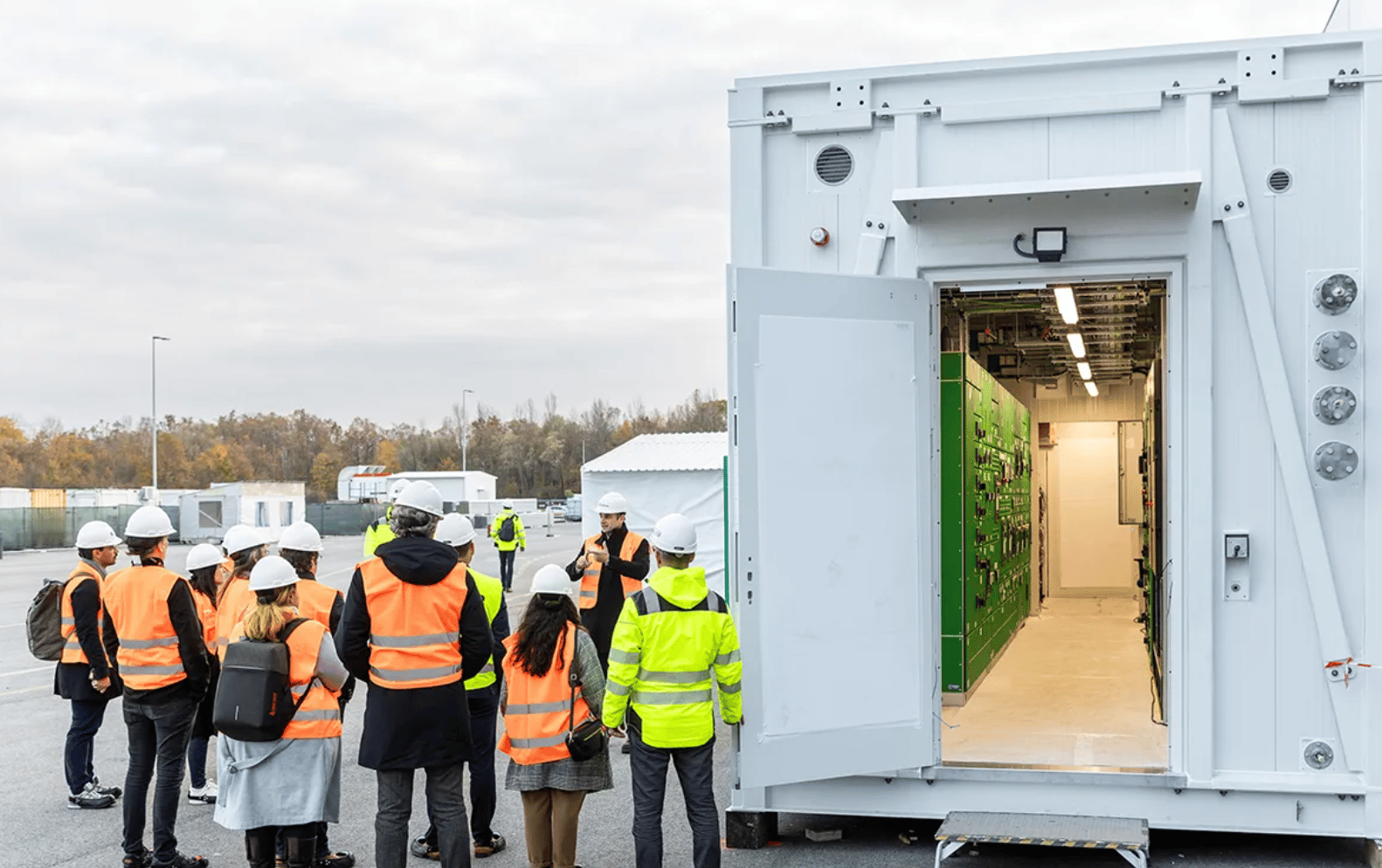

Move Four: Supply Chain Orchestration Across Labor Markets

Geographic Labor Arbitrage

Data center construction spans multiple geographies where labor costs vary dramatically: Virginia, Texas, Arizona, Ohio, and the Pacific Northwest all host significant facilities.

Katie described the approach:

"So where we have different labor in other locations, so we're doing offsite manufacturing there. So being able to use that local labor and then moving those skids with that equipment and things like that, where then the people who are installing it in the actual location, then they can just focus on that."

The logic:

If electrical labor costs 2x in Virginia but half in the Midwest, manufacture electrical racks in the Midwest

Truck finished assemblies east

Local crews handle final connections

Compress timeline and reduce cost simultaneously

This requires understanding regional labor markets and relationships with manufacturing facilities in labor-abundant regions. Most contractors lack this visibility.

What This Means for Technology

Geographic labor rate databases integrated into construction planning workflows remain sparse. Predictive models showing where prefabrication makes economic and schedule sense don't exist at scale. Technology that helps contractors identify manufacturing locations based on labor economics and supply chain factors provides real value.

Move Five: Owner-Furnished Equipment as Critical Path

The Coordination Challenge

In data center and semiconductor construction, owners supply substantial equipment. Most GCs treat OFE as something that "arrives." Fast movers treat it as a critical path driver.

Katie explained:

"Making sure we're really coordinated with that. And so especially in the data center world, I would say, a lot of the clients provide a lot of owner furnished equipment. And so making sure we're really coordinated with that. On the semiconductor side, they can provide some, a lot of times we'll buy a lot. So it's really working right with the full supply chain and making sure that all of those items are arriving when we need it."

The operational practice:

Weekly equipment reviews tracking vendor schedules

Proactive communication with vendors and owners

Dynamic schedule adjustments when delivery shifts

Early identification of risks

One delayed shipment consumes weeks of schedule buffer. If electrical equipment slips from week four to week six, the entire electrical trade sequence adjusts. The cascade effect means one supplier delay can domino across the project.

What This Means for Technology

Most project management tools treat owner-furnished equipment as passive. They show when equipment is scheduled but don't actively track equipment orders, vendor communications, or delivery dependencies. Technology integrating OFE tracking with site scheduling and flagging delivery risks early would solve a real problem.

The Hidden Multiplier: Culture Over Tools

All five operational moves rest on a foundation that cannot be purchased. Katie articulated it: "If everything works, we're probably not trying hard enough."

What Speed Culture Means

Willingness to try new approaches at controlled scale

Learning from iterations and building institutional knowledge

Cross-functional teams sharing real-time information

Rapid feedback loops where weekly reviews and daily adjustments flow back into planning

Comfort with structured experimentation

Katie described this approach:

"We try to try it in different controlled ways, obviously working with just our corporate emerging technology and teams as well so that we can try those out."

The company pilots new tools on one or two projects before broader deployment. They accept that some pilots won't work. They value the learning regardless.

The Tool Constraint

A scheduling tool cannot make a team more willing to try new approaches. A procurement platform cannot build vendor relationships. A prefab management system cannot create the safety mindset that moves work from height to ground.

Tools amplify culture. They do not create it.

Many construction companies buy tools and see no improvement. Tools expose process gaps, but culture determines whether gaps get addressed. Companies with speed cultures use tools to scale what they already do well. Companies without speed cultures struggle to benefit from tools.

This explains why some contractors achieve significantly faster timelines while others remain constrained to traditional schedules. The constraint is cultural discipline, not technical capability.

What This Means for Builders

The data center and semiconductor boom creates structural demand for speed. Clients have committed capacity to market. They face liquidated damages if delivery slips. They pay premiums for contractors demonstrating speed capability. This demand is structural.

Five Principles for Execution Speed

Understand workflows first. Speed isn't about individual tools; it's about operational sequences allowing parallel work, early coordination, and continuous adjustment. Execution succeeds by fitting into established sequences, not disrupting them.

Recognize speed as a symptom. Speed results from operational excellence removing waste and creating alignment. The goal is delivering projects safely, on budget, with quality.

Prioritize vendor relationships. Vendor relationships matter more in fast-track construction than traditional construction. Operations should deepen and scale relationships systematically, not treat them as transactional.

Integrate supply chain visibility. Treat owner-furnished equipment and supply chain visibility as central to execution, not afterthoughts. Coordinate prefab manufacturing with site sequences. Integrate vendor schedules with site schedules.

Build for geographic flexibility. Labor markets vary. Manufacturing locations matter. Execution planning should consider where work happens, not just when work happens.

The Question for You

In your current projects or operations, what is the single biggest operational bottleneck preventing faster execution?

Procurement cycles stretching across weeks?

Subcontractor coordination across geographies?

Supply chain visibility and vendor management?

Something else entirely?

Reply with the constraint you face most often. Understanding where real problems sit helps identify where operational improvements might create the most value.

Watch the episode with Katie Coulson here 👇👇👇

WEEKLY MUSINGS

Filler Images, Pre-release, Mega Projects

A major step for product visualization

Doing nothing is now the riskiest strategy

The infrastructure spending spree continues

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Premium Insights

More Insights

Reports and Case Studies

Most Popular Episodes

Super Series

OUR SPONSORS

Aphex - The multiplayer planning platform where construction teams plan together, stay aligned, and deliver projects faster.

Archdesk - The #1 construction management software for growing companies. Manage your projects from Tender to Handover.

BuildVision - Streamlining the construction supply chain with a unified platform for contractors, manufacturers, and stakeholders.