Want to go deeper? Join our Patreon community for exclusive, not publicly available content and support the future of architecture, engineering, and construction.

INDUSTRY INSIGHTS

Flux's $29m+ Failure - Lessons for the AEC Industry

Learning from failures is a powerful tool. Building on our "what went wrong" content (check out our previous post covering Modulous who spent £10m in one year), we've examined the story of Flux.

Despite raising a $29m Series B, Flux struggled to monetise effectively, which led to its eventual downfall.

But why? And what can we learn?

Let's explore.

In 2014, a group of innovative thinkers launched the first company to publicly emerge from Google X's incubator. Their aim? To improve building efficiency by streamlining the design process and enabling easy information sharing among users.

Flux's ambitious vision focused on solving one of the construction industry's persistent problems: data interoperability. The company aimed to create a seamless ecosystem where architects, engineers, and other stakeholders could share information effortlessly, similar to how Google's G Suite enables collaboration across various productivity tools.

At its core, Flux aspired to be more than just a software provider.

It aimed to become a platform where developers could build micro-apps, accessing data from various sources such as Revit, SketchUp, and Excel. This approach promised to create a rich, interconnected environment that could significantly enhance building design processes.

The ultimate goal was clear: by enabling better information sharing, Flux believed it could lead to the design and construction of superior buildings. This vision resonated with many in the industry who recognised technology's potential to transform traditional workflows and improve outcomes.

However, despite its grand vision, enthusiastic customers, and the clear problem it was addressing, Flux encountered significant challenges that would ultimately lead to its demise.

Business Model Issues

One of the primary challenges Flux faced was monetisation. The company initially adopted a freemium model, aiming to attract a large user base that could later be converted into paying customers.

However, this strategy proved problematic.

When Flux eventually introduced pricing, there was resistance from the user community, many of whom had grown accustomed to using the product for free.

Moreover, Flux found itself selling to the wrong decision-makers. While computational designers and tech-savvy professionals enthusiastically embraced the product, these individuals often lacked the authority to make purchasing decisions within their organizations. The disconnect between the users who saw value in the product and those holding the purse strings became a significant obstacle.

Industry-Specific Hurdles

The construction industry presented its own unique set of challenges. One of the most significant was a general reluctance to share data due to liability concerns. While Flux's vision was built on the free flow of information, many companies were hesitant to share even minimal data, fearing potential legal repercussions if shared data led to errors or disputes.

Anthony Buckley-Thorp, a former employee of Flux, highlighted this issue with a poignant observation:

"The Starry-Eyed dream that again I subscribed to was this free flow of information, right? Like if we can, the architect and the engineer and the client, we can all share information freely. We will be able to design better buildings. It's a simple fact. But the hard reality is that they don't want to share the data. They don't want to share a single byte more than they absolutely need to because they're exposing themselves to contractual risk."

This quote is significant. Construction is an industry prone to 'passing the buck', and this, unfortunately, was a key factor in Flux's downfall.

Furthermore, the construction industry's project-based nature posed additional difficulties. With projects often spanning several years, the sales cycle for construction tech products can be exceptionally long. This misalignment between the typical lifespan of a tech startup and the duration of construction projects created additional pressure on Flux's business model.

Lastly, Flux's collaborative approach conflicted with some of the traditional incentives in the construction industry. In an environment where companies often generate revenue through claims against one another, the idea of transparent, seamless collaboration was met with resistance.

User Adoption Struggles

Whilst Flux found enthusiastic supporters among early adopters and tech-forward professionals, it struggled to bridge the gap to mainstream users. Many potential users were more concerned with completing their daily tasks efficiently than adopting new, potentially disruptive technologies.

Additionally, there was often a disconnect between the value that computational designers and other tech-savvy professionals brought to their organisations and how these individuals were perceived by leadership. This undervaluation made it difficult for Flux to demonstrate its worth to key decision-makers who might not fully appreciate the potential impact of the technology.

The Pivot and Eventual Downfall

As these challenges mounted, Flux found itself at a crossroads. Despite having a product that users loved and substantial funding, the company wasn't able to achieve the growth and monetisation that its investors expected. In response, Flux made the difficult decision to pivot around 2018.

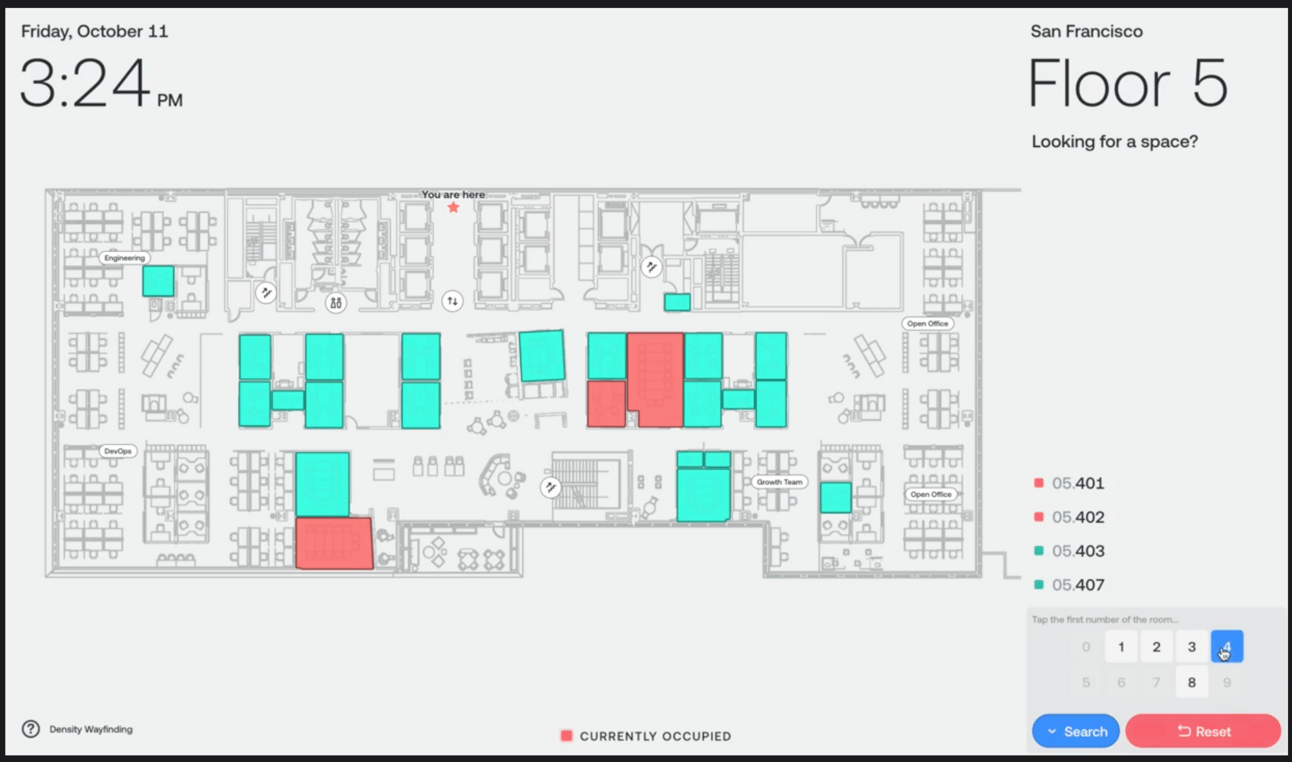

This pivot led to the creation of Helix, a new venture focused on digitising existing built assets. Whilst Helix found some success and was eventually acquired by Density.io, it marked the end of Flux's original vision.

The original Flux model, despite its innovative approach and enthusiastic user base, proved unsustainable in the face of industry realities and monetisation challenges. The company's inability to convert its technological achievements and user enthusiasm into a viable business model ultimately led to its restructuring.

Source: Density.io

Lessons Learned

Business Model Considerations - Freemium & Selling To The Right Person

One of the critical lessons from Flux's experience is the importance of having a clear monetisation strategy from the outset. While the freemium model can be effective in some industries, it proved problematic in the context of construction technology. Future startups should carefully consider how their pricing and business models align with the realities of the construction industry.

It's also crucial to identify and sell to the right decision-makers. Whilst end-users may love a product, if it doesn't resonate with those holding budgetary authority, scaling will be challenging. Startups need to ensure they're not just creating value, but demonstrating that value to those with purchasing power.

Understanding the Construction Industry

Flux's experience underscores the importance of deeply understanding the construction industry's unique characteristics. The reluctance to share data due to liability concerns, the project-based nature of the business, and the sometimes misaligned incentives all play crucial roles in how technology is adopted and used.

Future startups need to address these industry-specific challenges head-on. This might involve developing features that address liability concerns, creating pricing models that align with project-based workflows, or finding ways to work within existing incentive structures while gradually promoting change.

User Adoption Strategies

Bridging the gap between early adopters and mainstream users is crucial. Whilst having enthusiastic early adopters is valuable, it's essential to have a strategy for expanding beyond this initial group. This might involve creating different product tiers, offering extensive training and support, or gradually introducing more advanced features as users become comfortable with the basic functionality.

Moreover, startups need to demonstrate value not just to end-users, but to key stakeholders throughout the organisation. This might involve developing robust analytics and reporting features that can clearly show the impact of the technology on project outcomes.

Funding and Growth

Flux's story also offers lessons about the relationship between venture capital and construction tech. The expectations of rapid growth that often come with VC funding may not always align with the realities of the construction industry. Startups in this space might need to consider alternative funding models or work closely with investors who understand the unique dynamics of the industry.

It's also worth considering whether a "move fast and break things" approach, often favored in other tech sectors, is appropriate for construction. Given the high stakes and long-term nature of construction projects, a more measured "move carefully and improve things" approach might be more suitable.

The Legacy of Flux

Whilst Flux itself didn't achieve its original vision, its impact on the construction tech ecosystem has been significant. Many talented individuals who worked at Flux have gone on to found or join other innovative companies in the space. Startups like Speckle, Join.Build, Rayon, Hypar, Canoa, whilst not direct spin-offs, have been influenced by the lessons learned at Flux and are tackling similar challenges with new approaches.

Wrapping Up

The story of Flux, whilst ultimately not ending as its founders and investors had hoped, offers invaluable lessons for the construction tech industry. It highlights the unique challenges of bringing innovative technology to a traditional, complex industry, as well as the importance of aligning business models, user adoption strategies, and growth expectations with industry realities.

WEEKLY MUSINGS

VC Funding, The Ultimate Moat, Standardisation

A $50B boom on the horizon.

Trust, not tech.

Breaking down the myth

OUR SPONSORS

BuildVision — streamlining the construction supply chain with a unified platform for contractors, manufacturers, and stakeholders.